Conventional economic wisdom tells us that when interest rates rise, economic activity will slow. Interest rate adjustments (monetary policy) are the Federal Reserve’s main “policy lever” to control inflation, which is at its highest levels in decades in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The prevailing thinking is that businesses and consumers will borrow less as the cost of doing so increases. Conversely, these agents will borrow more when borrowing costs are low.

Baked into this line of reasoning is that the price increases we’ve seen over the last few years are demand-driven; households and businesses are so flush with cash (and apparently borrowing even more) that they’re competing with one another and bidding up the price of goods and services.

As shown in the graph below, the Fed lowered rates when the pandemic initially hit in hopes of spurring demand and combatting the recession. Since the beginning of 2022, it has rapidly raised rates in its effort to temper inflation by slowing demand:

While the rate increases have certainly affected the economy, I think it’s narrow-minded to believe that raising and lowering interest rates alone increases or decreases aggregate demand in the broader economy. Some parts of the economy may slow while others speed up. The relationship between interest rates and macroeconomic activity isn’t entirely clear or simple.

Mortgage applications and home sales, for example, have fallen off a cliff:

This intuitively makes sense.

The average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage today is 6.48%. With a 20% down payment on a $1 million home, the buyer’s monthly payment works out to around $5,000.

One year ago, the average 30-year rate was 3.22%. The monthly payment on the same $1 million house would have only been $3,500.

It’s no surprise that the rate increases have slowed the housing market — but what about the rest of the economy?

Despite constant fear mongering in the media about a coming recession due to interest rate hikes, the economy appears to actually be doing very well, with unemployment only around 3.5%, the lowest it’s been since the late 1960s. In a similar vein, Q3 GDP growth was over 3% and Q4 was over 4%.

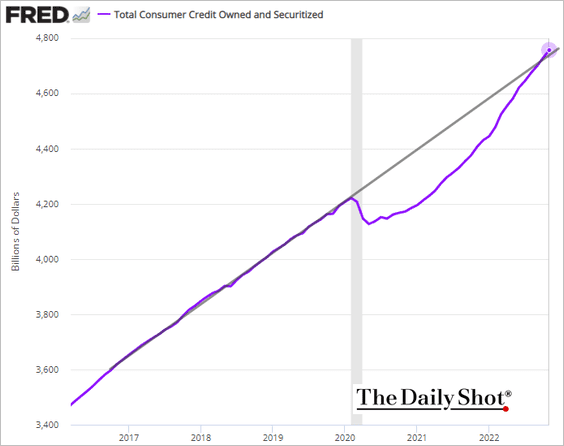

US consumer credit is above it’s pre-COVID trend even though credit card rates are higher than they’ve been in decades:

While this may seem concerning, lower-income households are actually allocating less of their total spend to credit cards than pre-pandemic according to Bank of America.

Again, this makes sense intuitively. Are credit card users actually sensitive to the variable interest rate on their cards? A recent Bankrate survey that found more than four out of ten credit card holders don’t even know what their card’s interest rate is, let alone how much it’s changed. With that in mind, it’s hard to believe the rate hikes are slowing demand by discouraging credit card spending.

The other side of the coin regarding rate increases that seems to be outright ignored by most of the financial media and economists is interest income on debt.

Look at what’s happened to the federal government’s interest expenditures as the Fed has raised rates:

Interest payments added up to more than an annualized $736 billion in Q3 of 2022 — a $220 billion increase over the same period just two years prior.

To put that into perspective, the US defense budget for all of 2022 was $722 billion.

Federal interest expenditures in 2022 are on pace to surpass the entire year’s defense budget.

Interest payments flow from the government to holders of federal debt — other government agencies, households, businesses, pension funds, you name it. This is free money from the federal government.

…but this is considered economic “tightening”?

It’s stunning how rarely this is discussed in the financial media.

Fiscal policy (taxing/spending), which Congress is responsible for, has a much greater impact on the macroeconomy than monetary policy, which the Fed oversees. However, the Fed is effectively engaging in major, albeit regressive, fiscal stimulus by increasing interest income throughout the economy via monetary policy.

Is this good policy? Not in my opinion.

Do we have to worry about a recession because of rate hikes? I think it’s quite the opposite.